Is Denver Altitude an Advantage for Denver Athletes?

Is competing at Denver altitude an advantage for the home teams? Is there less oxygen in the air that impairs performance for a sea level athlete?

The answer is mostly NO. What is in the air by average altitude has been well documented. While the atmosphere can vary by weather system, these relationships and implications mostly stay the same, at least with respect impairing performance for a visiting team. Basketball in Tibet is another story.

Oxygen in the air remains at a constant percentage of 20.94% in the air no matter what the altitude. So why do the athletes who come up from sea level feel there is less oxygen?

Respiration, or the exchange of gasses in the lungs, depends upon the pressure of the gas going in versus the gas going out through the membranes of the lungs. As one goes higher in altitude, there is simply less partial pressure of the gas. At sea level, the average barometric press of the atmosphere is 760 millimeters of mercury (mmHg). At 5,000 feet, this drops to 632 mmHg. So it is slower for O2 to pass through the lungs. However, research concludes this might make breathing a bit more labored. Yet, there is no decrement in aerobic or endurance performance. You have to get above 6000 feet before seeing a 3% loss in aerobic performance. Not a factor in coming to Denver.

The reason that it feels more challenging to breathe is water.

The amount of water vapor in the lungs that helps respiration is the key. At sea level, this is approximately 47 mmHg of that barometric total. In addition, the nasal passages and throat add some additional water vapor during inhalation or taking in air. In New York City, the average humidity in the air is 63%. In Denver, the average moisture in the air is much less than 50%, often only 25%. That difference means that lungs don’t have the same respiratory support and transference from natural humidity in Denver.

During moderate or higher-intensity exercise, the lungs can lose 65 milliliters of water per hour. Drop the humidity, and the lungs over time hydrate the surfaces internally to aid respiration. It is not a simple mechanical system where the lungs instantly respond, hence one of the factors in altitude acclimatization.

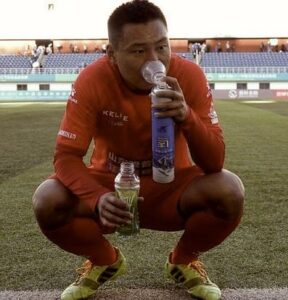

Does inhaling oxygen at altitude help?

Some studies show that in training activities like interval training, adding oxygen at crucial times positively increases training adaptations over time. However, during a performance, as a running back taking it to the house, getting oxygen on the sidelines might be more mental than physical. One thing not studied- does the oxygen supplementation get the athlete to breathe more deeply, which results in getting more carbon dioxide out? Deep breathing on its’ own between athletic bouts has a positive effect on recovery.

Both supplemental oxygen and hyperbaric training chambers have shown mixed, mostly minimal results if at all, in relation to VO2 or endurance performance.

Probably the most beneficial strategy for athletes coming to Denver is “swishy” hydration. Simply taking in little bits of water in the mouth but not drinking it all down will help add moisture, i.e., water vapor, into the lungs. The result will be a better transfer of oxygen in/carbon dioxide out. Sleeping with a humidifier might provide additional comfort and short-term acclimatization if there is a night before the contest. On the sidelines, holding a towel close to the face wetted with distilled water will have an effect, as some moisture can get to the lungs. You have seen some athletes chewing on a wet towel on the sidelines. It might not taste great, but the water source is closer to the lungs.

The lungs can’t breathe precisely the way they do at sea level at even a moderate altitude like Denver. The research has shown it takes almost three weeks to fully adapt to Denver altitude specifics. Or the athlete just comes in and plays within a day or two, and no acclimatization is needed.

In short, what athletes experience when they play in Denver coming from sea level is more psychological than physiological. The reduced humidity makes athletes feel they can’t get oxygen, which is false. The lessened humidity is the real factor, and in some athletes creates symptoms similar in feeling to exercise-induced asthma. Those humidity-boosting strategies can help negate that “I can’t breathe feeling.”

Once the mind understands the bit of a dry throat, performance tends to return to normal.

References

Bannister R, Cunningham D. The effects on the respiration and performance during exercise of adding oxygen to the inspired air. J Physiol 125: 118–137, 1954.

Ploutz-Snyder LL, Simoneau JA, Gilders RM, Staron RS, Hagerman FC. Cardiorespiratory and metabolic adaptations to hyperoxic training. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol. 1996;73(1-2):38-48.

Welch H, Mullin J, Wilson D, Lewis J. Effects of breathing O2-enriched gas mixtures on metabolic rate during exercise. Med Sci Sports 1: 26–32, 1974.

Etheredge C, Judge LW, Bellar DM. The effects of a personal oxygen supplement on performance, recovery, and cognitive function during and after exhaustive exercise. J Strength Cond Res. 2014 May;28(5):1255-62.

DeCato TW, Bradley SM, Wilson EL, Harlan NP, Villela MA, Weaver LK, Hegewald MJ. Effects of sprint interval training on cardiorespiratory fitness while in a hyperbaric oxygen environment. Undersea Hyperb Med. 2019 Mar-Apr-May;46(2):117-124.

Adams RP, Welch HG. Oxygen uptake, acid-base status, and performance with varied inspired oxygen fractions. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol 49: 863–868, 1980.

Illidi, C.R., Romer, L.M., Johnson, M.A. et al. Distinguishing science from pseudoscience in commercial respiratory interventions: an evidence-based guide for health and exercise professionals. Eur J Appl Physiol (2023).

Dempsey JA, La Gerche A, Hull JH. Is the healthy respiratory system built just right, overbuilt, or underbuilt to meet the demands imposed by exercise? J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020 Dec 1;129(6):1235-1256.

Winter FD, Snell PG, Stray-Gundersen J. Effects of 100% oxygen on performance of professional soccer players. JAMA 262: 227–229, 1989.